A bridge from Broadway's back rooms to prestige TV

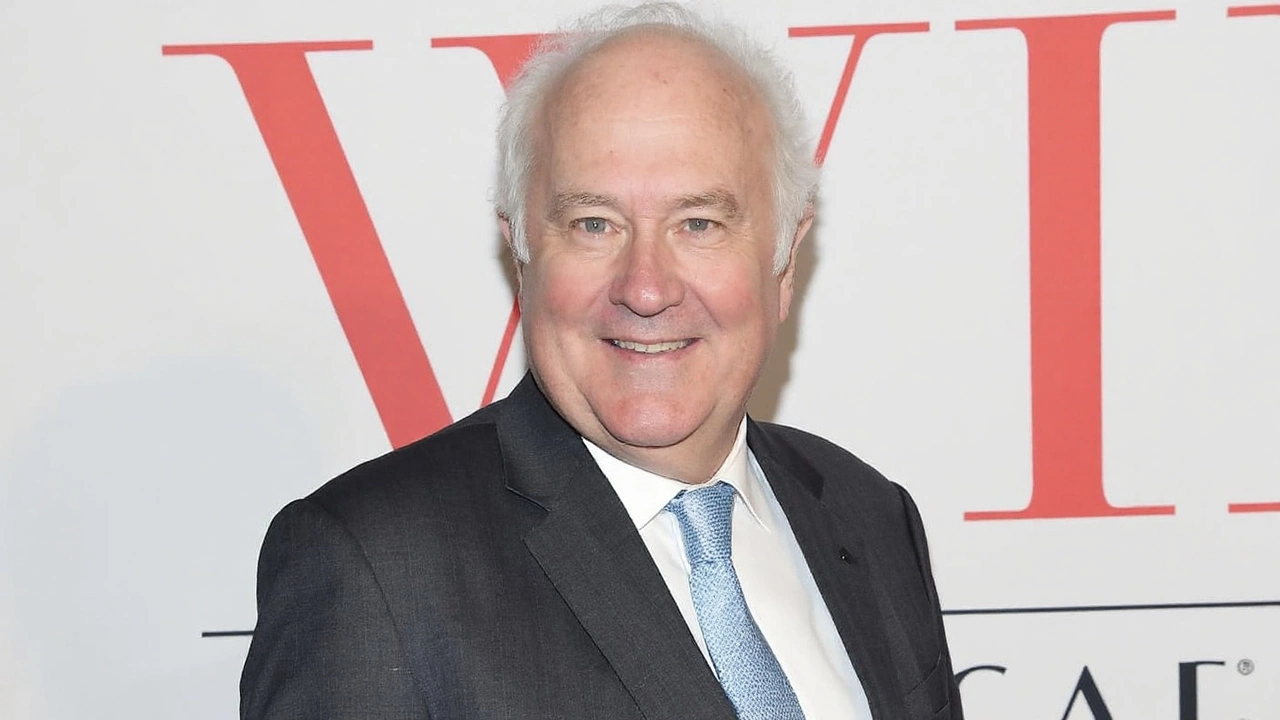

Jerry Adler, a steady hand in American entertainment who moved from backstage legend to late-blooming screen actor, died on August 23, 2025, at his home in New York City. He was 96. His death was confirmed by Riverside Memorial Chapel.

Adler was a familiar presence to two generations of TV viewers. On HBO's 'The Sopranos,' he played Herman 'Hesh' Rabkin, the sharp, old-school adviser whose counsel Tony Soprano sought when the room needed history, tact, or a reality check. He appeared across all six seasons, often easing heavy scenes with dry wit that hid real steel. On CBS's 'The Good Wife' and its spin-off 'The Good Fight,' he played Howard Lyman, a partner whose rumpled charm, institutional memory, and surprising decency became a fan favorite. He was that rare actor who could turn moral ambiguity into a shrug and a smile without losing the stakes.

His route to those roles was anything but typical. Born on February 4, 1929, in Brooklyn, Adler grew up in a tight-knit, Yiddish-speaking household steeped in theater. This was not show business from the outside looking in; it was the family business. His father, Philip Adler, served as general manager for the Group Theatre and many Broadway productions, the kind of job that meant solving problems in the rehearsal room, the box office, and everywhere in between. His great-uncle was famed Yiddish theater star Jacob Pavlovich Adler. A cousin, Stella Adler, became one of the most influential acting teachers of the 20th century.

Adler liked to joke about how he got his start. As he told TheaterMania in 2015, he was at Syracuse University when his father called: there was an opening as an assistant stage manager on 'Gentlemen Prefer Blondes.' He took the job and never looked back. 'I skipped school,' he said. It was the kind of career pivot that sounds impulsive, until you remember he was stepping into a family trade.

For decades, Adler lived backstage and thrived there. Before he ever landed in front of a camera, he had already worked on 53 Broadway productions as a stage manager, production supervisor, producer, or director. He had a hand in shows that became part of Broadway's common language, including 'My Fair Lady,' 'Camelot,' 'Annie,' 'The Apple Tree,' 'Black Comedy/White Lies,' and 'Coco.' These were not just credits; they were hard jobs that require judgment, stamina, and a talent for keeping the art intact when everything around it gets messy.

By the time he decided to try acting on camera, Adler was in his 60s. He liked to say he thought he was 'too goofy-looking' to be an actor, and the surprise never quite left his voice when he talked about being recognized on the street. But the camera liked him, maybe because he never pushed. He showed up like a man with a lifetime of rehearsal in his pocket and did the work.

Film directors took notice. He popped up in 'Manhattan Murder Mystery' and 'The Public Eye,' later in 'In Her Shoes' and 'Prime.' On television, he became a reliable guest star who could slide into a show and immediately feel like he belonged. On 'Mad About You,' he played Mr. Wicker, the building's maintenance man with impeccable timing. He did arcs on 'Rescue Me,' 'Transparent,' and 'Broad City,' and traded deadpan with Paul Rudd on 'Living With Yourself.' The roles varied. The effect did not: he grounded scenes without making noise about it.

The roles that stuck: Hesh Rabkin and Howard Lyman

Hesh Rabkin was never the loudest man in the room on 'The Sopranos,' and that was the point. He was a reminder that everything Tony Soprano struggled with had a past, and that much of that past was written by people who looked for leverage, not glory. Hesh knew the music business and the street, and his counsel could be empathetic or brutally transactional depending on the day. Adler played him with a softness that could turn on a dime, which made those scenes feel lived-in rather than staged. When he showed up, the air changed.

On 'The Good Wife,' Howard Lyman was different but cut from the same cloth in one key way: he belonged to the institution before the stars did. He was a partner with quirks, a bit of a throwback, but consistently human. Adler found the humor without turning the man into a joke. On 'The Good Fight,' he returned to that world and, in the process, underlined what made him so valuable: he could walk into a complex ensemble and instantly set the tone.

What tied those roles together was the craft he learned in all those years backstage. Stage managers and directors think in beats, space, and timing; they see the play from every seat in the house. Adler carried that perspective onto sets that prized detail. He understood how to serve a scene, not just a line. That is why writers liked to write for him and why castmates trusted him.

He never left the stage behind. Adler returned to Broadway as an actor twice late in life: in 2000 in 'Taller Than a Dwarf,' and in 2015 in Larry David's 'Fish in the Dark.' Both were comedy-forward, both needed a player who could thread humor through a scene without stepping on it. He did that with the economy of someone who had spent decades listening from the wings.

In 2024, he pulled the curtain back on the long view. His memoir, 'Too Funny for Words: Backstage Tales from Broadway, Television and the Movies,' charted a career that touched three different versions of the same business: the Yiddish-inflected theater culture of his childhood, the Broadway of mega-hits and meticulous craft, and the era of prestige television where character actors became anchors. The stories doubled as a quiet argument for the value of second acts. You can spend half a lifetime learning one side of the business and then find a new way to belong to it.

Adler's roots were never an ornament. He was raised observant, in a home where Yiddish was spoken and theater was not just work but heritage. He went to Samuel J. Tilden High School in Brooklyn, where he ran the Dramatic Club, and later to Syracuse University before that call from his father changed the plan. The family throughline matters here: the Group Theatre, Stella Adler's training, Jacob P. Adler's legacy in Yiddish theater. This is an American theater story told through a single family, and Jerry Adler's life stitched it to modern television.

He did not chase fame. He chased the job. Even when recognition arrived late, he treated it like an odd side effect of doing the work right. Colleagues remember the reliability: he hit his marks, he lifted scenes, and he made space for everyone else to be good. If you want a word for that in show business, the best one is rare.

Key milestones that sketch the scope of his career:

- Born February 4, 1929, in Brooklyn, into a family deeply rooted in Yiddish and American theater.

- Leaves Syracuse University to become assistant stage manager on 'Gentlemen Prefer Blondes.'

- Spends decades backstage, working on 53 Broadway productions in management and creative roles, including 'My Fair Lady,' 'Camelot,' 'Annie,' 'The Apple Tree,' 'Black Comedy/White Lies,' and 'Coco.'

- Begins on-screen acting in his 60s, building a steady portfolio in film and television.

- Breakout TV roles as Hesh Rabkin on 'The Sopranos' and Howard Lyman on 'The Good Wife' and 'The Good Fight.'

- Returns to Broadway as an actor in 'Taller Than a Dwarf' (2000) and 'Fish in the Dark' (2015).

- Publishes a memoir in 2024, reflecting on a career that spanned theater's backstage and television's spotlight.

Adler's death closes a living link between Broadway's postwar heyday and contemporary television's golden run. He lived both realities from the inside: the logistical ballet of building a Broadway hit and the quiet power of serving a TV scene without drawing attention to the work. You see that link most clearly when you watch him in a late 'Sopranos' episode or an unruly conference room in 'The Good Wife.' He listens first. Then he lands the line.

Plenty of people in entertainment get one chapter. Adler made three. The backstage chapter was built on patience and precision. The acting chapter proved that presence can outperform flash. And the final chapter, where he looked back in print, offered a map for anyone wondering if it was too late to start again.

He once said that seeing himself on film felt strange after so many years out of sight. That was his sense of proportion talking. Fame passes. The work sticks around. If you watch the right scenes, you can still see the stage manager in him, measuring the beat, leaving room for the next person to land their moment.

He is gone at 96, but the throughline holds: a life in the theater that made television better. For fans of 'The Sopranos' and 'The Good Wife,' the face is familiar. For Broadway lifers, the name means something different and just as lasting. For anyone who has ever switched lanes mid-career and wondered if it could possibly work out, it is proof.