Grand Rapids Priest's Communion Ban on Lesbian Judge Ignites Debate

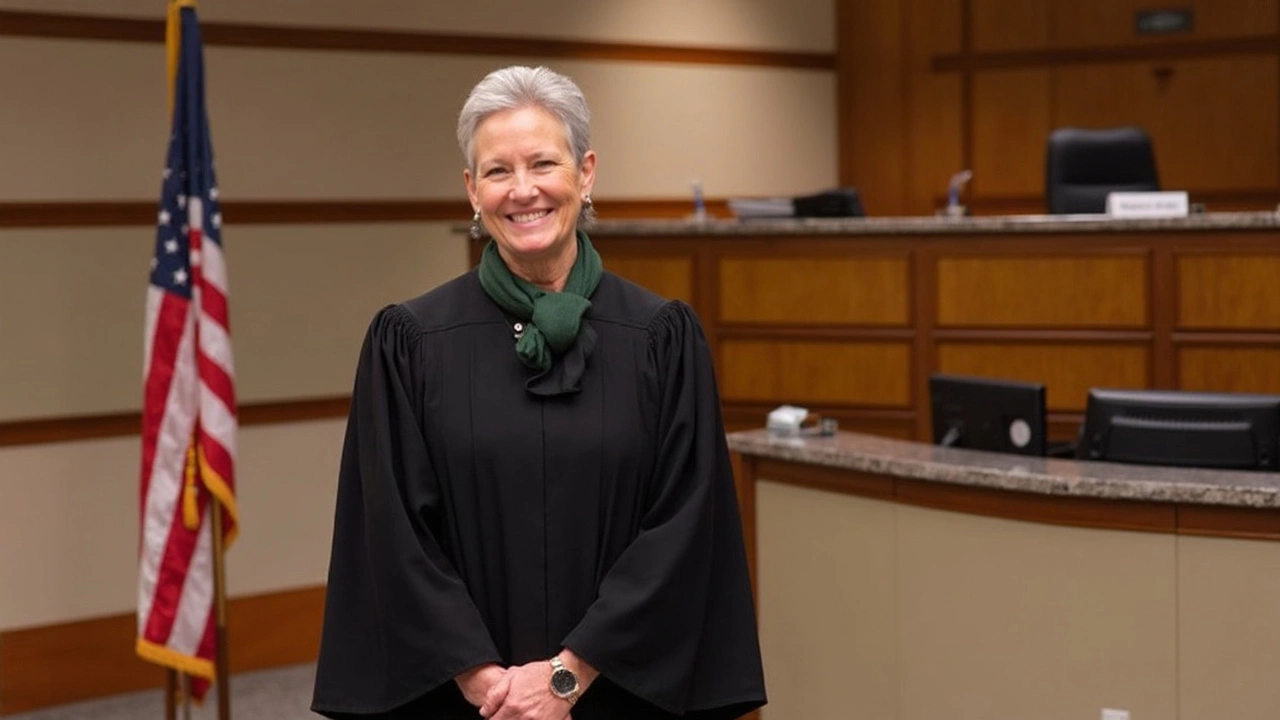

When Father Scott Nolan, pastor at St. Stephen Parish in East Grand Rapids, told Judge Sara Smolenski that she could no longer receive Communion, the fallout rippled far beyond the church walls. Smolenski, a respected Kent County judge and lifelong Catholic, had never imagined her decades of worship in the pews would end like this—all because she married her partner, Linda. The issue wasn't just about a single sacrament or parishioner; it put the Grand Rapids Diocese, and the larger Catholic community, squarely in the national discussion over how faith, tradition, and LGBTQ identity collide.

It all happened in November 2019. The story broke after Smolenski explained how she was barred from Communion, not in front of the congregation as some news outlets reported, but in a private conversation initiated by Father Nolan. He called her, stating bluntly she couldn't receive the Eucharist given her same-sex marriage. The directive came as a shock. Smolenski remembers feeling "pushed out," yet her sense of faith held strong—a part of her life she wasn't ready to let go, even now.

As word spread, parishioners and the wider community voiced strong reactions. For some, it was confirmation that Church doctrine would not budge, no matter the personal cost. For others, it represented a painful barrier to LGBTQ inclusion, with many pointing out what they saw as a pattern of exclusion, not just a one-off decision. Smolenski was not the first LGBTQ Catholic to feel sidelined by **Grand Rapids Diocese** policies—but she was among the most visible, given her record of public service and long history in the parish.

Diocese Doubles Down on Doctrine Amid Criticism

Within days of the controversy erupting, the Grand Rapids Diocese released a statement defending Father Nolan. According to Church leadership, being part of a Catholic community requires public alignment with its teachings—especially on marriage, which they still define strictly as a covenant between a man and a woman. The diocese said allowing those who openly disagree with this core belief to fully participate in the sacraments would "undermine the community's faith." In their words, this wasn't an act of singling out or exclusion, but a necessary step for the sake of doctrinal integrity.

Critics saw things differently. Some accused Nolan and the diocese of practicing systemic discrimination, pointing out that LGBTQ Catholics often feel unwelcome or even ostracized—not just at St. Stephen's but in parishes across the region and country. Smolenski herself described her treatment as deeply painful but emphasized that she still considers herself a person of faith, regardless of institutional barriers. Supporters and detractors clashed on social media, at parish meetings, and in public forums, revealing just how raw and unresolved the debate really is.

This case made people across Michigan—and beyond—question how religious tradition and modern understandings of identity and family can coexist, or if they even can. The diocese, for its part, remains firm: upholding Church teachings comes first, and public actions that contradict doctrine will have consequences. For LGBTQ Catholics like Smolenski, the personal cost of that stand is anything but theoretical—it’s a lived reality, and one that isn’t changing anytime soon.